Introduction

It’s a fairly common characteristic of people who go into science research that we love to talk about science and share our knowledge. But as I’ve studied science communication, especially as it applies to science outreach, I’ve come to realize that the approach taken by most scientists, presenting information from their field through talks and demonstrations, rarely gives people any deeper understanding of science. To achieve meaningful interactions with non-scientists, especially when doing science outreach, I believe scientists must step back from the role of presenter and into the role of facilitator.

This series of webpages, continued below and on three subsequent pages, documents the design process I went through to create a game (my modifiable machine demo) that would help me to step into that facilitator role. I hope you find these notes helpful as you create your own outreach tools, or as you build your own version of the modifiable machine.

Often, designing a good tool is half the battle.

Designing to encourage facilitation

Since these topics have their own subsections I won’t go into too much detail. The work that I did can largely be divided into physical design (designing for specific audience, designing an open-ended activity) and communication design (adapting my content/style for a target audience, facilitating with an open-ended activity). I believe these choices do a lot of the work to get both me and my activity participants engaging with activity in a way that lets the participants guide the activity as much as I do.

The Modifiable Machine Game

You can find out about my modifiable machine demo on a different part of my website (there’s even designs there if you’re feeling inspired to make your own). This demo highlights my sub-fields within chemistry, separation science and designing machines for science research. I go into more detail on the science here, but briefly: separation science is the science of physically sorting items according to differences in their size, shape, mass, or chemical makeup. At the most basic level, the machine is a gate that collects and releases balls of different shapes down a height-adjustable ramp. But I could develop many different presentations using this model. My goal in building the demo was to present guests with a game with a centered around a relatively open-ended separation problem (how can you separate the balls in this bag using only this simple machine I’ve built?). I encourage them to use iterative, hypotheses-driven experiments to improve their machine and “solve” the problem. I’ve found that the game is great for engaging participants on topics like scientific uncertainty and experimental design that are fundamental to many areas of science research.

The modifiable machine in action

Presenting vs Facilitating

What does it mean to facilitate rather than present? Presenting on science is a largely one-way transfer of information from an expert to a non-expert. Owing to the one-sided sharing of information, only knowledge available to the presenter is conveyed to the audience. Although many presentations create additional spaces for dialogue between the presenter and the audience, such as a Q&A portion, these dialogues are often directly influenced by the information shared during the presentation. Presenters therefore, have a lot of power to determine what dialogue, if any, they have with their audience.

It is possible to present my modifiable machine to an audience. For example, I could send balls down the ramp to illustrate how some shapes roll more easily than others. I could use this demo during a presentation on my own work, to show how a scientist might build a machine to sort objects of different shapes. Again, though, my audience has no input over what the demo does. They are beholden to the information I choose to share.

Presenting on my research to an audience. Although there was a Q&A, it largely focused on points I raised during the talk. Thus, even in the dialogue, I did the bulk of the decision-making.

Alternatively, I can choose to facilitate my audience interacting with science through my demo. Like presenting, facilitating requires me to make design and communication decisions (as you will see if you navigate to the other pages in this section). Unlike presenting, facilitating a scientific demo requires space for the audience to leverage their own backgrounds and experiences. Because the audience are asked to be active participants and make choices about what to do with the demo, they step into a scientist-like role. When I supply information as a facilitator, beyond the basic machine setup, it is in response to my participants. Rather than creating a presentation based entirely on what I think my audience will find most relevant, I can facilitate an activity that creates a dialogue between my participants and myself in which I no longer have the privileged role.

Outdated Models and Facilitating Public Engagement with Science

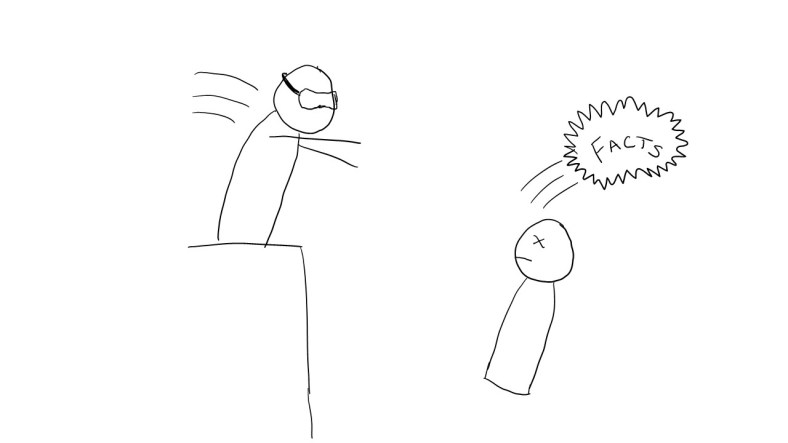

Scientists are knowledge experts by design; one of our jobs as scientists is to gather facts. When talking about science with a person on the street, it’s incredibly easy to turn any discussion into a lecture because you just know so much and you’re excited to share that knowledge. I know that when I started doing outreach I assumed that if I just showed people how cool science was, they’d have to be as into it as me. This assumption is one of the many faces of the deficit model of communication and as a communication method it’s a hard habit to shake.

The author in her youth, engaged in an aggressively outdated method of science outreach with her audience

The deficit model of communication has its roots in expert-lay communication, risk management, and decision making. For a significant portion of the 20th century, decisions about new technology, education, health etc. were made by experts for lay people. Here, an expert was someone with an educational or professional background in the scientific area in question; these experts occupied positions of power such as government official, doctor, or scientist. A lay person was anyone who lacked that background. Lay people were expected to accept and follow expert opinions and decisions.

However, a number of health and environmental tragedies showed that this model of communication and decision making was deeply flawed. (For one great example, see “Sheepfarming after Chernobyl” by Brian Wynne.) Communication scholars began to recognize that expertise comes in many forms. When so-called experts ignore what are sometimes called lay epistemologies (the ways of knowing about a topic that come from a person’s culture, background, values, priorities, etc.) they often alienate the very groups they’re attempting to help. Instead of an expert-lay interaction, researchers began to argue that engaging groups in scientific dialogue was key to decision making.

Since then, studies of public engagement with science have provided new ways to increase the dialogue between those who conduct science research and those who have a stake in the outcomes and impacts of that research (which in today’s world is everyone). Public engagement was developed by observing and reflecting on the intersection of science and society:

- People have different perspectives that are informed by their experience. These different perspectives mean that all individuals can be considered experts in their own lives. These different perspectives also mean that there is no monolithic public that scientists speak to.

- The different perspectives of individuals or communities, when combined with the perspective of scientists, can bring new insight to, among other things, scientific research or the management of new science technology.

- By encouraging different groups, including scientists, to engage with the ideas of others on scientific issues, we can create more robust fields of study within the sciences and within the use of science and technology in society.

Strategies that encourage public engagement can also increase public understanding of science, literacy or trust in science, although these largely depend of the quality of the public engagement.

Public engagement strategies are well-served by the facilitation of science demos. In particular, by focusing on play as a form of public engagement, it’s possible to encourage public engagement with science among children, especially with the process of scientific discovery. Facilitating game asks participants to engage with the game by making decisions that affect its progression. Beyond facilitating participants’ understanding of scientific concepts, game play can also help develop:

- Skills that aid in social activities that relate to science

- Social and cultural understanding of science

When the game mimics the scientific method or the process of designing and using experiments, it will encourage participants to interact with the scientific method in a manner similar to scientists. In the case of my machine demo, the game asks participants (mostly children) to engage with the process of scientific research. They are asked to briefly role-play as the scientists and make changes to the machine that they think will have the change they desire. In doing so, they are developing a sense of how scientists conduct experiments to acquire new scientific knowledge.

My Communication Background

Although I’ve undergone other science communication training, my framework for how I think about communication largely comes from work I did as part of the Science, Technology, and Society Studies (STSS) certificate program. The STSS field is, among other things, the study of the process of science. STSS was one of the first fields to challenge the deficit model of science communication. My focus in the program was to learn how scientists and science mediators (think businesses that use science, the media, museums) talk about scientific research. I also wanted to learn how I could communicate science more effectively by seeking out and responding to the interests of the people I interacted with. What I have learned in this program is strongly reflected in many of my design choices, and some key lessons will be discussed in more detail there.

I also learned many practical science communication and demo design skills from the Pacific Science Center. They run a great program that takes scientists from around the greater Seattle area and trains them in the essentials of science communication in museums. In particular, I developed the physical demo and some of the preliminary work on facilitating (like asking questions to guide discussions) during my time in that program.

Why am I posting all of this online?

Since a sample size of 1 person (me) is hardly a sample at all, I want to inspire you to build this demo for yourself and let me know of your successes (and failures). I came into this project with very specific design goals; to make an activity aimed at middle- and elementary-school-aged girls that would give them an opportunity to learn more about how scientists build and test machines. As a learned more about science communication, this morphed into a demo I use to help people step, however briefly, into the role of a scientist. I hope the work I did adapting my demo to facilitate those experiments will help you as you design a version of this demo that meets your needs.

How can you get more information?

Whenever possible, I’ve tried to make my experiences more applicable to the general science outreach facilitator. However, it would be disingenuous for me to say I came up with all or even many of these ideas by myself. To that end, I’ve creating a reading list here of some papers and books you might find helpful or interesting as you develop your own outreach tools.