As I mentioned in the introduction, I wanted to develop a communication tool that would help participants step into the role of a scientist and confront some common science research problems. To make my demo more effective, I made physical design choices that helped it to target a particular audience and better model the open-ended nature of science research. In this section, I want to discuss the decisions I made about how best to communicate these concepts with my demo. Whenever possible, I wanted to step into the role of a facilitator, someone who would help guide participants towards satisfying conclusions using the demo without giving them the answers.

The Demo, in brief

An overview of how my demo works can be found here. Briefly, I ask participants if they would like to help me work on my scientific machine. If they say yes, I bring them over to my machine and tell them that I can use the machine to release balls down the ramp. I ask them if they can help me change it so that I the balls come off the ramp in the same order every time. I tell them I have multiple sets of balls we can try and ask them to choose one set. The first time they try rolling balls down the ramp it looks something like this:

Unlike more typical types of public engagement, where people bring their expertise as non-scientists to a scientific topic, I ask non-scientist to step into the role of a scientist, not as a producer of facts but as a user of the scientific method and an observer of some uncertain phenomenon. By observing how the machine separates the balls and predicting how changes to the machine might change the race, participants engage with “science” as a scientist might. Participants often observe that scientists, through machines represented by this demo, exercise control over their experiments, and use that control to help make predictions. The hope is that this engagement not only helps them to develop a better understanding how scientists view problem-solving and research, but also as a jumping off point to discuss the limitations of science research and scientific discovery. This developed understanding and skills can then be used to enhance individual’s engagement with new scientific and technological discoveries.

Goals

Like in my physical design section, I created a set of communication goals that I try to draw on in each interaction. The communication strategies I discuss below are targeted to help my participants achieve one or more of the following goals:

- See that experimental results can be unpredictable; discuss the idea of experimental reproducibility

- Predict (correctly or not) the outcome of an experiment using a machine they designed

- Be able to rationalize (again, correctly or not) the prediction made in the previous goal

It’s possible that these goals will not resonate with you and you’ll want to make your own. If you’re new to making goals for an outreach activity, I made this quick guide that I hope will help you as you create goals for this or another outreach activity you do.

Creating an Open-ended Demo

Although creating an open-ended demo sounds like a physical design goal, how you introduce your demo to your participants can have a huge impact on how they interact with it. First, I try not to overwhelm my participants with choices or information. After presenting the basic machine to them (as discussed above), I ask them what they would like to do next. If I get a blank stare, or they ask me what to do, I’ll give them two suggestions to pick from. This keeps the choice from being overwhelming while also ensuring they are still guiding the interaction.

Next, I try to ask a lot of good questions. A good question is a piece of art; hard to make. Good questions ask a participant to pause and reflect on what they have learned, and possibly make choices in response. Whenever possible, good questions also are asked in response to something your participant said to you. Some of my go-to questions include:

- “What did you observe?”

- “Do you think that will happen a second time if we repeat the experiment?” (more on that in the next section)

- “What do you think will happen if we make that change? Is there a different change you’d like to try?”

Finally, I always encourage my participants to test out the ideas they share, so long as they’re not dangerous. Some participants seem dubious that there is not a right answer that solves the problem posed by the machine. By encouraging them to test out their ideas, I’m trying to show them that no test is a bad one. This helps to reinforce that the demo is designed for open-ended exploration.

Facilitating Engagement with Uncertainty

There is a difference between uncertainty in a decision (non-technical uncertainty) and uncertainty in the results of science research (scientific uncertainty). When scientists talk about this scientific type of uncertainty, it is easy for non-scientists to interpret this as non-technical uncertainty. From the first design of my demo, I knew I wanted to try to incorporate uncertainty into how I talk about my demo, to give my participants experience with scientific uncertainty.

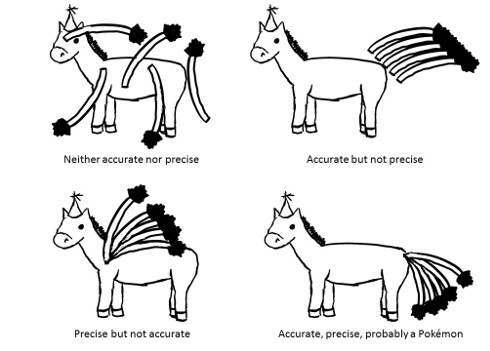

Uncertainty can be thought of in two ways, accuracy and precision. The accuracy of the data is how close it is to the correct answer (in the image below, an accurately placed tail is one that is on the correct part of the donkey). We can talk about the accuracy of a single experiment, but it is more common to discuss the accuracy of multiple tests; how close is the average of all those tests to the correct answer. The concept of “right answers” is debated and very research-question specific, so I ignore it in favor of focusing on precision. Precision is a measure of how reproducible your result is (in the picture below, the results are precise if the tails end up in nearly the same place each time, even if that spot is “incorrect”). Regardless of whether you have an accurate result, a precise result is one where the same test repeated multiple times yields the same answer. In other words, precision/reproducibility is a measure of the predictability of your experiment.

Accuracy vs precision at a 5-year-old’s birthday

So how can I use my demo to facilitate participants learning about uncertainty? First, I try never to lead with the idea of uncertainty. I introduce the idea of reproducibility after they have run an experiment once or twice. That way, they know to expect from an experiment. I can then ask them some variation of “If we run the balls down the same ramp with the same setup multiple times, do you think you’ll get that result every time?”

If my participant answers yes, I encourage them to run the same test again. This demo machine is not that precise, especially in its most basic design, and so they oftentimes will get a different answer. I’ll then raise the question: “Do you think we could design a machine where we could feel more certain of the outcome?” Typically, that initiates a conversation about changing the machine to make the result more reproducible (increasing the machine precision). At this point, I’ve not only introduced reproducibility and tied it into how the machine/experiment is designed. As always, since I am in the facilitator role, I let the person I’m interacting with decide how deeply we discuss uncertainty from there.

Communicating to a Specific Audience: the benefit of flexibility and asking questions

If you haven’t done a lot of science communication, it can be tempting to lump all non-scientists into the same group. But as I mentioned in the introduction, every audience you encounter will be made of individuals that bring their own unique perspective to the conversation. In your role as a communicator, it’s good practice to try to understand the values and background of your audience so that you can establish a dialogue with your participants and help them engage with the research you’re discussing.

Fortunately, I would argue it’s easier as a facilitator to establish this connect with your audience than as a presenter. As a facilitator, asking questions like “Have you ever encountered x in your daily life?” or “How do you feel about y?” can give you basic insight into someone’s background. As you establish a dialogue with your participants, it’s then easier to adapt your conversation to their interests. As a presenter, you have less flexibility to engage in this sort of dialogue.

When you think you’re going to encounter a specific audience, there is some prep work you can do. For example, because I made physical changes to my design to make it of interest to young girls visiting the museum, I expected many of them will participate in my demo (this was a correct expectation). To ensure they would get the most out of the demo, I tried to facilitate the following:

- Social interaction: whenever possible, get participants talking to each other

- Female role models: there’s research suggesting I do this by existing, but I also try to talk about all the other great female scientists I know

- Using inclusive language: I went for gender neutral pronouns whenever possible

- Encouraging creativity: avoid guiding participants to a solution or test unless they look lost

- Avoiding a right answer: see my discussion of uncertainty for more detail

If you’re interested in designing for a difference audience, I highly encourage you to dig around online to find design tips for that target group.

Hopefully reading through my communication strategies gives you some insight into how you can better step into the role of a facilitator in your own outreach work. As always, for more information from experts in the science communication field, I encourage you to visit my recommended reading page.